This is New Manchester Walks’ first virtual tour. It’s all we can do at this time, sadly, but we love to give good value. So sit back, bring to your mind the geography of the area around Manchester Town Hall, and soak in the history on this section of our ingenious “Undiscovered Manchester” walk that we plan to run when things return to normal, using the real-life route and a history highlight at each stop.

Go to Central Library, St Peter’s Square, for an 11.15 start

- Manchester Central Library

Designed by Emanuel Vincent Harris, best known for the bleak concrete fortress that is the Ministry of Defence on Whitehall, it was opened in 1934 at a ceremony presided over by George V. The king was annoyed that when he gave the royal knock at the main door the librarian inside dropped the key and took an age to open up. The event is marked with a white stone plaque.

Harris had cleverly chosen to model the building on the Pantheon. Not just the well-known Pantheon of Rome (a link is that the Library is in St Peter’s Square), but also the recently demolished and lesser-known Pantheon of London. That magnificent building dated back to 1772, and was designed by James Wyatt, who was also the architect of Manchester’s St Peter’s Church (1794) that stood where the memorial cross, visible from the Library, stands.

Such astonishing links…See the IloveMcr website for the full story.

Now cross to the Midland Hotel

- Midland Hotel

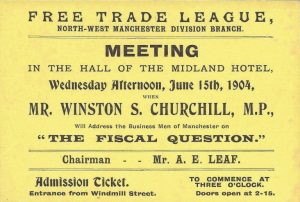

It is not obvious standing in Peter Street that Manchester’s most famous hotel was built for the railways. The former Central Station is at the back though the two buildings should have been linked. The hotel opened in 1903 and soon attracted the glitterati. Winston Churchill spoke here in June 1904, a month after Rolls and Royce didn’t meet here (a subject we’ll deal with anon), and stayed on 4 January 1906 while campaigning to win the seat of Manchester North West. He was then a Liberal, who were in opposition, but expected to walk the forthcoming general election. Edward Marsh, his secretary, recalled:

“We walked out to take the air following our noses and finding ourselves in the slums. Winston looked around him and his sympathetic imagination was stirred. ‘Fancy living in one of these streets – never seeing anything beautiful, never eating anything savoury, never saying anything clever.’”

We couldn’t find a picture of Churchill at the hotel in 1906, but here’s the ticket from an earlier speech there.

Head to Mount Street

- Mount Street

When you’re standing half-way along Mount Street you can see the three buildings of Manchester city centre that the Nazis targeted not to be bombed during the Second World War: the Town Hall, Midland Hotel and Central Station. They were fully convinced that Unternehmen Seelöwe (Operation Sea Lion) – invasion of Britain – would be successful, and these were the building they wanted for their own ends. Could they be that accurate with their bombs? It has been proved since the War that the Nazis had 70% accuracy, and interestingly neither building was properly hit.

The Nazis never did invade, but how did they know so much about this little slice of Manchester? In the 1930s, before the War, the bar was regularly propped up by Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, and one of his major lieutenants, William Joyce. While the former spent much of the War in jail for his political activities, Joyce spent the War based in Berlin, working for Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda department disseminating the Nazi line on the wireless.

Head to the back of the Midland Hotel

- The Peterloo Memorial

It’s only been up year, created to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Peterloo Massacre (see below), and so it’s possibly still too early to give an honest appraisal of artist Jeremy Deller’s handiwork. Interestingly the very name “Peterloo”, when coined by the Manchester Observer newspaper on 21 August 1819, came with a revelation that introduced the concept of an artist into the mix:

“It is rumoured, and we believe it correct, that orders have been sent to an eminent artist for a design to be engraved for a medal, in commemoration of Peter Loo victory.”

Note two words: Peter Loo.

Head west along Windmill Street to the corner with Southmill Street

- The Hustings/Tree of Liberty

It was at this very junction that the hustings, two wooden carts spliced together, was placed on Monday 16 August 1819 when a crowd of 60,000 people came for a summer’s day out and maybe for some political speeches. Unfortunately the authorities chose not to let this happen and sent in the military to arrest the speakers and violently disperse the meeting. There was carnage, with at least a dozen deaths on the day and more victims as the days went by. This was the Peterloo Massacre, the most violent even in British political history.

Incidentally on the very site, the junction of Windmill Street and Southmill Street at the back of the Free Trade Hall, there stands an unassuming tree. It reminds me that two hundred years ago “trees of liberty” were rife in Scotland, France and America as meeting places for radicals. The original Liberty Tree was a famous elm that stood in Boston and was used by rebels as a rallying point in the run up to American independence. As this tree is positioned at such an important political location, it should become Manchester’s Tree of Liberty

Head along Southmill Street to Peter Street

- The Suffragettes on Southmill Street

It was on this short street on the evening of Friday 13 October 1905 that a group of women who would later be derided as “suffragettes” gathered as a public meeting in the adjacent Free Trade Hall, called by the Liberal opposition in the run-up to an imminent general election, came to a close. The women, led by Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney, had been ejected from the meeting for deliberately disrupting it. They wanted the next Liberal government to give votes to women. No chance.

- Interestingly for psephologists on the stage that night were four future prime ministers:

– Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the only PM ever to die inside No. 10

– Herbert Asquith, the only PM to have got married in Manchester

– David Lloyd George, the only PM to have been born in Manchester

– Winston Churchill, not the only PM to have been an MP for Manchester

- Free Trade Hall

There’s so much to say about what is not only Manchester’s most important building but one of Britain’s greatest…except that only a small portion of the previous four building remains.

Let’s clarify. Richard Cobden and his free trade merchants built a small wooden building called the Pavilion on the site in 1840. It was replaced by a brick structure only two years later. When Cobden and his supporters won their battle for free trade in 1846 the occasion was marked with a banquet attended by some 3,000 guests who at midnight were treated to a rousing rendition of the song “There’s A Good Time Coming, Boys”.

To celebrate further, a new hall was erected, of which the grand Italianate façade, based on the Gran Guardia Vecchia in Verona, is all that’s left, the rest of the building having been destroyed in the Second World War Blitz. Of the fourth 1951 hall, which so many Mancunians remember from Halle and rock concerts, only some relics remain. They’re hidden away, although we show them on various tours.

Cross Peter Street by the Peterloo plaque and head along the continuation of Southmill Street

- Peterloo Wall

On the right (Town Hall) side you will see the back wall of the Friends’ Meeting House. A bricklayer who came on one of our Peterloo Massacre tours assured us that the wall dates back to the 18th century. That means it witnessed the terrible day, 16 August 1819, when Mancunians were cut down for demonstrating for the right to vote. Ordinary people fleeing the weapons of the troops were mercilessly attacked here. Sam Bamford, who organised a huge contingent from Middleton to come to the meeting, recorded what happened:

“A number of our people were driven to some timber which lay at the foot of the wall of the Quakers’ meeting house. Being pressed by the yeomanry, a number sprung over the balks and defended themselves with stones which they found there. A heroine, a young married woman of our party, with her face all bloody, her hair streaming about her, her bonnet hanging by the string, and her apron weighed with stones, kept her assailant at bay until she fell backwards and was near being taken; but she got away covered with severe braises.”

The wall has been the home for various articles and graphics related to Peterloo in recent months, so well done Friends Meeting House for responding to our idea. The wall might well have been there on Peterloo day, but the building wasn’t. It is post-Peterloo, dating back to 1828.

Continue along Southmill Street as it bends to the right

- Memorial Hall

On the right, at the junction of Southmill Street and Albert Square, stands the glorious Venetian-styled brick frontage of the Memorial Hall. The building was designed by Thomas Worthington, who was also responsible for the nearby Albert Memorial and water fountain in Albert Square.

Worthington beat Alfred Waterhouse in the competition to build Manchester Town Hall but was stymied. The Memorial Hall is a fitting alternative. It was built from 1863-66 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the birth of nonconformist Protestantism – that Protestants could worship without being bound by the strictures of the Church of England. The use of different coloured stones and the shape of the windows give this a Venetian feel, as opposed to the Flemish Gothic of the nearby Town Hall. There are similarities with the famous Ca’ d’Oro of Venice.

The influence here is John Ruskin, the most powerful figure in the development of English architecture in the 19th century. In books such as The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849) and The Stones of Venice (1853) Ruskin explained how:

“in one point of view Gothic is not only the best, but the only rational architecture, as being that which can fit itself most easily to all services, vulgar or noble. Undefined in its slope of roof, height of shaft, breadth of arch, or disposition of ground plan, it can shrink into a turret, expand into a hall, coil into a staircase, or spring into a spire, with undegraded grace and unexhausted energy; and whenever it finds occasion for change in its form or purpose, it submits to it without the slightest sense of loss either to its unity or majesty”.

Turn tight onto Albert Square, past the restaurants that include Rajdoot Tandoori, just about the only remaining traditional night time curry house in the city centre, and cross Mount Street into Lloyd Street.

- Three Herons

Look up at the Lloyd Street side of the Town Hall when entering from Albert Square. On the wall between the corner with Albert Square and the side entrance to the building there are three herons carved in stone. They are tribute to Sir Joseph Heron, town clerk of Manchester in the mid-19th century, who presided over the works in one of the greatest municipal enterprises in British history.

Continue along Lloyd Street, marvelling at how Emanuel Vincent Harris, who we met earlier, segued his 1930s bridges so adroitly that they look like they went up with the original.

- Town Hall Extension

You’re now at the Town Hall Extension, like Central Library designed by Harris. It opened in 1938; it had to open in 1938 as it was created to mark the centenary of Manchester’s running its own affairs with a democratically elected council. There were other stipulations; the design had to be neutral, not to detract from the Gothic of the Town Hall or the Romanesque of the Library. Cheekily Harris simply chose one of his earlier designs. The similarities with his own Atkinson’s Scent Shop on Old Bond Street, London, are uncanny.

Atkinson’s, Old Bond Street, not the Town Hall Extension

Atkinson’s, Old Bond Street, not the Town Hall Extension

- Back at Central Library

Now you’re back where we started at Central Library. At the beginning we saw the George V tablet by the main doors. George V opened the library in 1934. On the other side of the door there is a tablet dedicated to Ramsay MacDonald, Labour prime minister in 1930, who laid the foundation stone on 6 May 1930.

The two men endured a fraught relationship from the moment Ramsay Mac became prime minister for the first time in January 1924. The king was distraught that the Labour Party delegates had sung “The Red Flag” and “La Marseillaise” at the Albert Hall a few days earlier. The new prime minister apologised and explained that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. The king was unimpressed and explained to Ramsay Mac that if any Labour minister wanted an audience with him they had to wear full dress suit and knee breeches. Robert Morrison, the MP for Tottenham, calculated that to attend court functions he would have to spend £57 including “nine guineas for the regulation sword. If I had known that such gorgeous dresses would be worn I would have gone to Tottenham Fire Brigade and borrowed a helmet and tunic for the occasion.”